“Feed a gut, and starve a fever” or friendly vs disease-causing pathogens

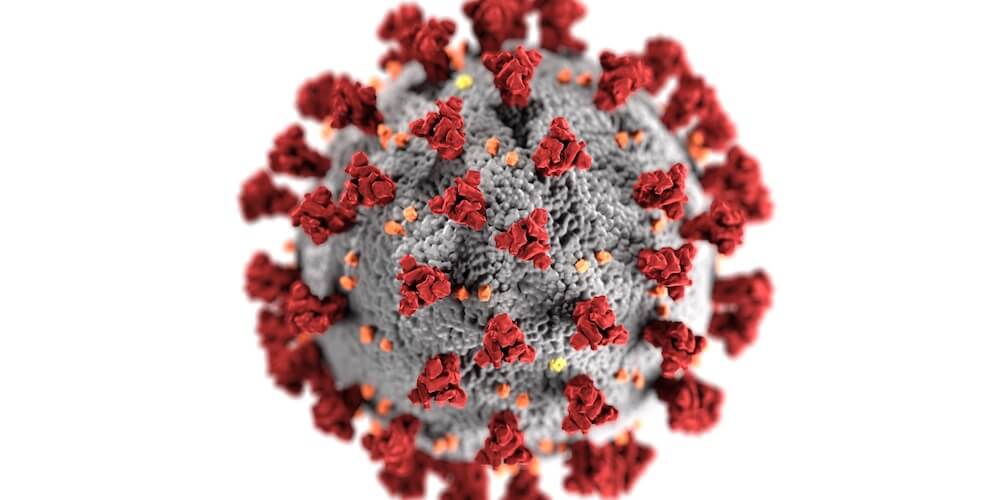

The Swedish Pathogens Portal focuses on bacteria and viruses that pose a threat to human health and well-being. However, the definition of a “pathogen” is not easy. The word “pathogen” is usually reserved for microorganisms capable of causing disease when most people are exposed to them for the first time without preventive measures. These kinds of pathogens are, however, a vanishingly small fraction of the total amount of microbes in our world. In addition, infections are the result of the interplay between a microbe and a host. Whilst most people do not get seriously sick from most interactions that they have with microbes, for a sufficiently weakened host, such as a premature baby, even yoghurt could pose a serious threat.

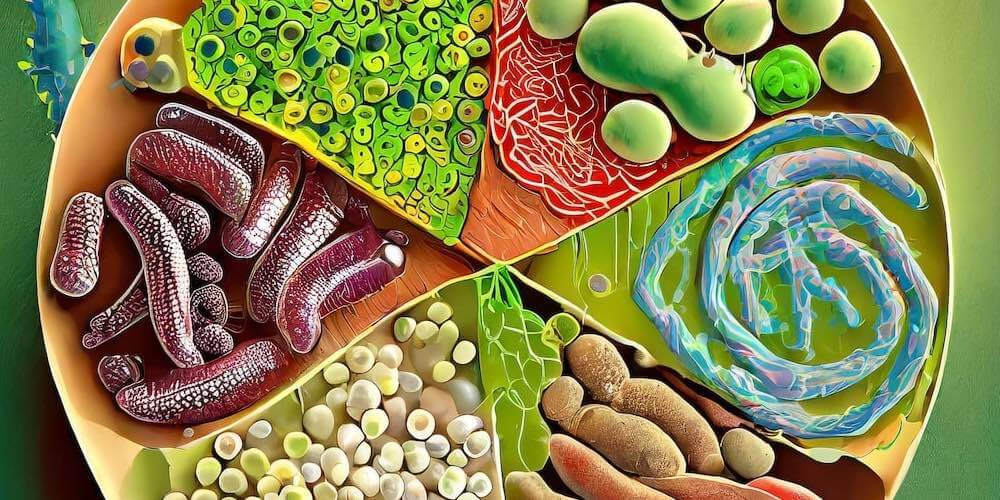

The vast majority of microbes simply won’t survive on our bodies – it is either too dark, too dry, too exposed, too moist, even too nourishing. Each living organism – including microorganisms – thrives in a specific niche, which includes their preferred range of light, oxygen, pH, sugars, and other small molecules. Still, a couple of thousand species do enjoy a temperature around 37°C, a wide availability of carbon compounds, and varying amounts of oxygen – there is a lot on our skin and lungs, and very little to none in our bowels. Our ancestors have been living and co-evolving with these species since before the first humans evolved. Some of the most important interactions between our bodies and our microbes can also be found in some form in many other mammalian specials. This means that scientists are able to observe patterns in humans, test them in animals, and then refine our hypotheses for the next round of human studies.

While all body surfaces (both internal and external) are covered with microbes, mostly bacteria, the density of microbial cells at different body sites varies; from a couple of cells per ml in the stomach to billions in the lower bowel. This is mostly mirrored by the microbial diversity in these body sites as well. Our stomachs typically have either one species, Helicobacter pylori, famous for its role in driving the development of gastric ulcers, or a few Lactobacillus species that are able to survive in this very acidic environment, but don’t really thrive. Meanwhile, the large bowel will typically harbour somewhere between several hundred to a thousand different species, with a higher species diversity being typically connected to good health. Eating a variety of vegetables, whole grains, and nuts gives our gut bacteria a wide menu of different fibres to digest, creating many small niches for different health-promoting species. Conversely, a low-fibre diet, lack of exposure to nature and the outdoors, and continuous or repeated use of medication may drive away certain species, leaving in its wake an impoverished and more fragile ecosystem, susceptible to additional threats in the form of antibiotics or invasive bacteria.

One body site that is an exception to the “more microbes – more diversity” rule is the vagina of pre-menopausal women where, despite the women having a dense microbial community, a lower diversity is associated to good health. This is also a prime example of a mutually beneficial symbiosis, where the mucosal cells are filled with nourishing glycogen that sustains Lactobacillus species, and they in turn secrete lactic acid and other substances that lower the pH and protect against infections.

For all practical purposes, an infant’s microbial colonisation begins at birth. A number of processes during pregnancy prepare the newborn to their new life outside the womb. This preparation continues during breastfeeding, as human milk contains an astounding variety of different sugar molecules that cannot be digested by humans – but are very well digested by the Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species that colonise the infant gut. Even live bacteria are included in breast milk, transported to the milk ducts by special cells called dendritic cells, which are experts at transporting microbes across the body. Normally, they do this to warn our immune systems of any danger, but they can also take live bacteria to where they need to be. In the infant gut, bacteria will help them to digest food, occupy niches otherwise left open to pathogens, interact with the developing immune system to help it to learn what is dangerous and what is harmless, and secrete countless small molecules that will interact with the developing brain and other organs. Bacteria in the gut is most crucial in the first one to two years of life, but even as adults we have a thriving bacterial community that can help us to thrive as individuals as well.

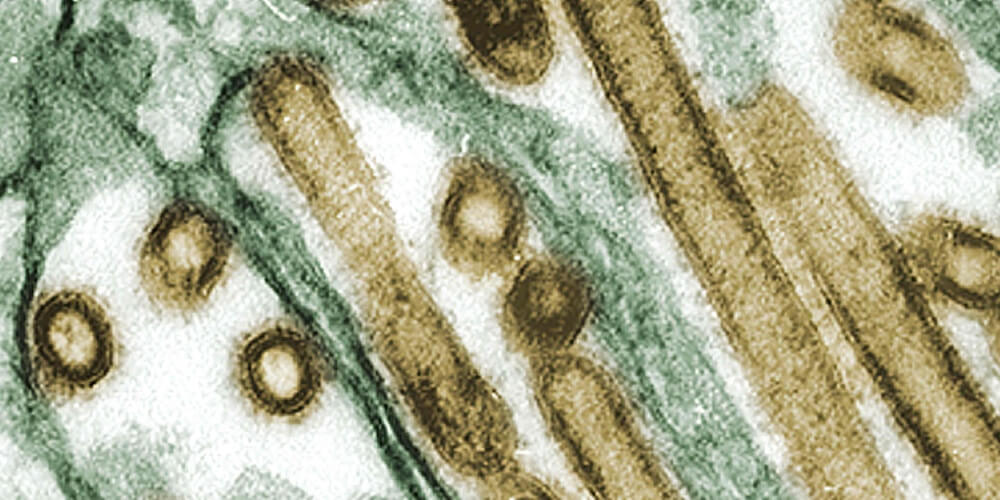

Whilst the disease-causing pathogens, often classified as part of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, worms, viruses, and even infectious proteins called prions, are a vanishingly small fraction of the total amount of microbes in our world, they still pose a health threat to millions of people on a daily basis. Pathogens can be our best friends, or worst enemy. An old saying is “Feed a cold, starve a fever", but feeding our friendly microbes just might prevent that cold entirely! The complexity of pathogens, while extensively studied, still warrants much more reseach.

Cite this editorial

Hugerth, L. W. (2024). Editorial: “Feed a gut, and starve a fever” or friendly vs disease-causing pathogens. SciLifeLab. Online resource. DOI: 10.17044/scilifelab.25217921.